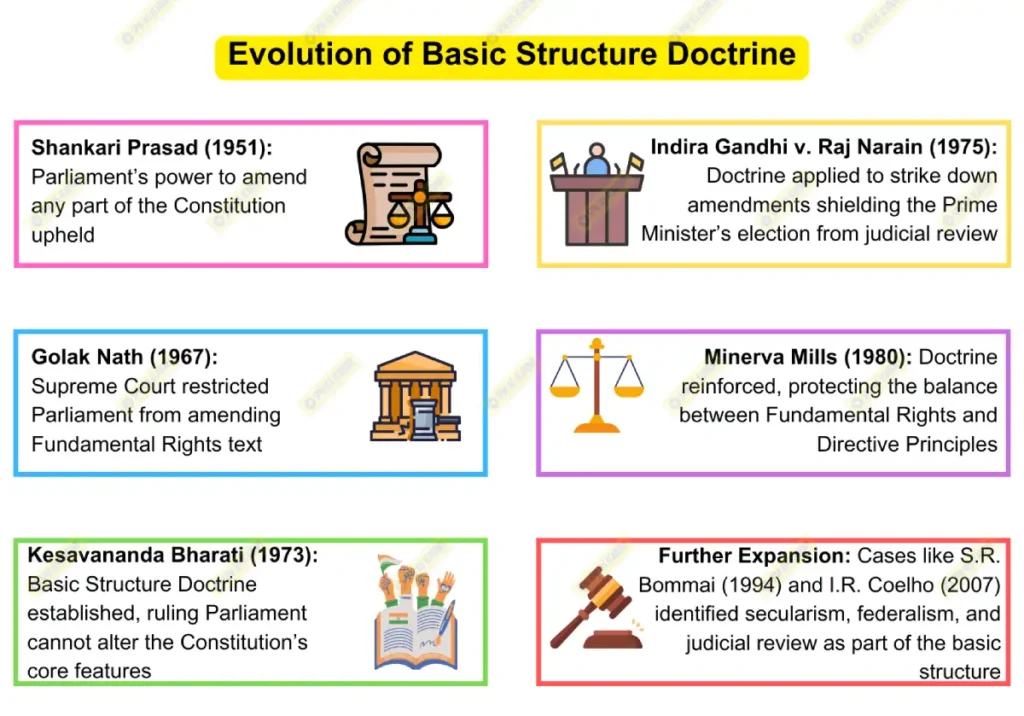

The ‘basic structure’ doctrine of the Indian Constitution is a judicial principle safeguarding the Constitution’s core values from potentially harmful amendments. Established in the landmark Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) case, the doctrine asserts that while Parliament can amend the Constitution under Article 368, it cannot alter its fundamental framework. Since its inception, this doctrine has sparked significant debate regarding the balance of power between the judiciary and the legislature. Recent comments by Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar have further added to this ongoing discourse.

Key Elements of the Basic Structure

The judiciary has progressively identified elements that make up the Constitution’s basic structure, though no exhaustive list exists. These include:

- Supremacy of the Constitution

- Sovereign, democratic, and secular nature of the Indian state

- Federalism and judicial review

- Fundamental rights and parliamentary democracy

These elements, embodying the principles set forth in the Preamble, provide the foundation for India’s constitutional framework and protect its democratic ethos.

Different Views on the Basic Structure Doctrine

Over time, various Supreme Court judgments and perspectives from eminent jurists have contributed to a wide-ranging debate on the basic structure doctrine. The recent remarks by Vice President Dhankhar bring contemporary relevance to this discussion:

1. Supportive View of Judicial Safeguards

- The Kesavananda Bharati judgment established the basic structure doctrine, with then-Chief Justice S.M. Sikri describing it as a necessary constitutional safeguard. Justice H.R. Khanna emphasized that the Constitution is a “living framework” that requires protection from arbitrary changes.

- Legal scholars like Nani Palkhivala have praised the doctrine as “constitutional insurance” for citizens, arguing that judicial oversight is essential for preventing legislative overreach and upholding democratic integrity.

2. Concerns over Judicial Overreach

- Critics argue that the doctrine grants the judiciary excessive power, potentially infringing on parliamentary sovereignty. In Indira Nehru Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975), the Supreme Court struck down the 39th Amendment, which attempted to exempt the Prime Minister’s election from judicial scrutiny. The Court held this amendment as unconstitutional under the basic structure doctrine, which led to concerns about judicial encroachment on legislative authority.

- Recently, Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar echoed these concerns, arguing that the judiciary’s application of the doctrine may at times restrict Parliament’s mandate and infringe upon the balance of power. Dhankhar’s comments reflect a viewpoint that advocates for limiting judicial intervention to ensure legislative autonomy in amending the Constitution.

3. Debate on Flexibility vs. Rigidity

- In Minerva Mills v. Union of India (1980), the Supreme Court reaffirmed the doctrine, ruling that Parliament cannot use its Article 368 powers to destroy the basic structure. However, Justice P.N. Bhagwati cautioned that excessive rigidity could hinder the Constitution’s adaptability, as constitutional reforms may be needed over time.

- Scholars like Granville Austin also argue that while the doctrine is necessary for protecting foundational values, a highly restrictive interpretation may obstruct progressive amendments. Austin’s perspective calls for a flexible interpretation that allows for essential social and economic reforms while preserving core principles.

4. National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC) Recommendations

- The NCRWC (2000), chaired by Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah, endorsed the basic structure doctrine as vital for preserving constitutional values. However, the Commission recommended a balanced judicial approach to prevent “excessive judicialisation” and ensure that Parliament retains sufficient power to enact necessary reforms aligned with evolving needs.

- The NCRWC also suggested that certain elements of the basic structure be clarified to reduce ambiguity and improve judicial consistency. This clarity would give Parliament adequate space to pursue meaningful amendments without compromising core principles like democracy and secularism.

Recent Perspectives and Public Debate

Vice President Dhankhar’s comments have reignited debate on the basic structure doctrine, questioning the extent of judicial oversight over parliamentary power. By advocating for greater legislative flexibility, Dhankhar reflects concerns that expansive judicial interpretation may impede parliamentary reforms. The basic structure doctrine, established in the Kesavananda Bharati case, safeguards democracy, secularism, and fundamental rights against legislative overreach, yet must balance judicial and legislative roles. Insights from the NCRWC and jurists like Justice Verma emphasize a balanced approach, ensuring that the doctrine protects constitutional principles while allowing legislative innovation essential for India’s progress.