Why in the News?

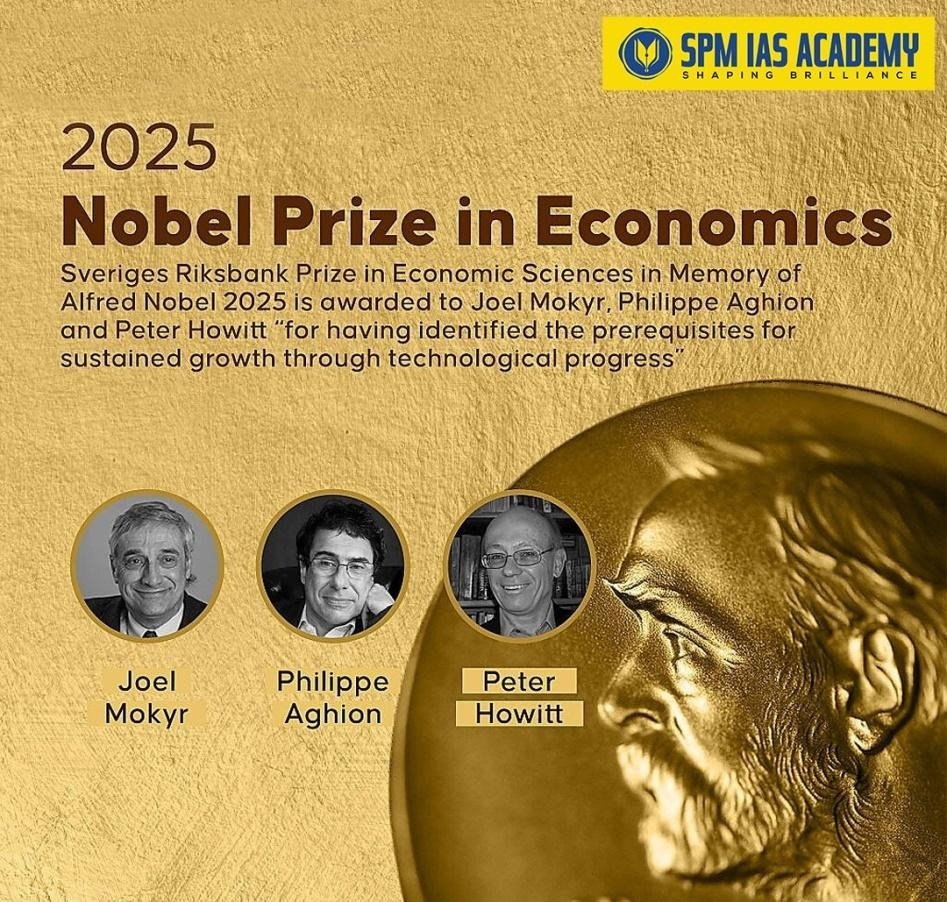

On 13th October, 2025, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the ‘Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2025 to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth and historical contribution.” It is also known as the Nobel Prize in economics.

What Is the Nobel Prize In Economics And Its History?

- Notably, the Nobel Prize in Economics was established to honor research that improves human understanding of economic systems and societal welfare.

- Prior to this, in 1968, the Nobel Prize in Economics was established by Sveriges Riksbank, which funded a donation to the Nobel Foundation on the occasion of its 300th anniversary. As a result, for the first time in 1969, the prize was awarded and institutionally aligned with other Nobel Prizes.

- It focused on theoretical and empirical analysis of economic processes, including growth, trade, and consumption. Earlier, it emphasized on quantitative modeling and dynamic economic systems. However, it has expanded in scope to include behavioral economics, governance, welfare, and development.

- Additionally, the award comes with prize money of 11 million Swedish kronor (Rs 10.25 crore).

- This time, the half of the prize money has been awarded to Mokyr, and the remaining half will be shared between Aghion and Howitt.

Who Are The Awardees Of Nobel Prize in Economics, 2025 And What Are Their Contributions?

1. Joel Mokyr:

- Provided that one of the awardees of the Nobel Prize in Economics, 2025, is Joel Mokyr. Further, he is an economic historian. Additionally, his work utilized historical sources to uncover the causes of sustained economic growth worldwide.

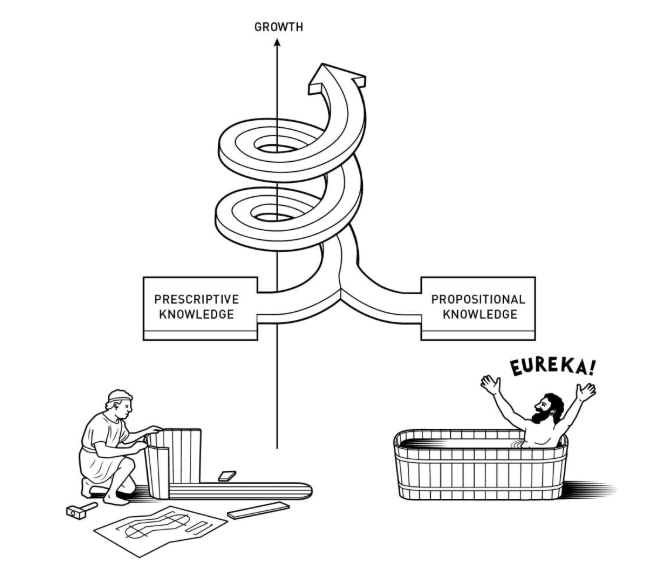

- He showed that prior to the Industrial Revolution, technological innovation was primarily based on “prescriptive” knowledge i.e. people often knew “how” things worked.

- However, they did not have the answer to “why” things worked (Mokyr calls this as “propositional” knowledge).

- But this changed over the 16th and 17th centuries as the world witnessed the Scientific Revolution as part of the Enlightenment.

- According to Mokyr, scientists began to insist upon precise measurement methods, controlled experiments, and that results should be reproducible. Accordingly, this led to the “how” and “why” queries getting answered to produce “useful” knowledge.

- Joel Mokyr examined why earlier periods of human history failed to generate sustained economic growth. However, his research on long-term development reveals that innovations often remain isolated. In addition, societies lacked the institutional and intellectual frameworks needed to build upon them systematically.

- In fact, Mokyr distinguished between two essential forms of knowledge for continuous progress: prescriptive knowledge—the practical know-how of what works, and propositional knowledge—the scientific understanding of why it works.

- Before the Industrial Revolution, societies possessed fragmented practical skills but lacked the scientific foundation to explain and expand upon them.

Mokyr’s research highlights three key conditions necessary to break free from this cycle:

- In general, society should promote the parallel growth of scientific knowledge and its practical application. It was seen during the 16th and 17th century Scientific Revolution, which paved the way for the Industrial Revolution.

- However, a group of skilled artisans and entrepreneurs is essential to translate innovative ideas into products.

- In addition, institutions must remain open to new ideas and adaptable to the disruptions brought by technological progress. For example, in the Enlightenment era, bodies like the British Parliament fostered greater acceptance of change.

2. Philippe Aghion And Peter Howitt

- Furthermore, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt formalized the concept that economic growth sustains itself through the process of creative destruction.

- In fact, creative destruction refers to the process in which innovations replace older technologies. For instance, smartphones are replacing flip phones and digital cameras are overtaking film cameras.

- Aghion and Howitt’s 1992 model demonstrated that this is not merely technological change, but a fundamental driver of sustained economic growth.

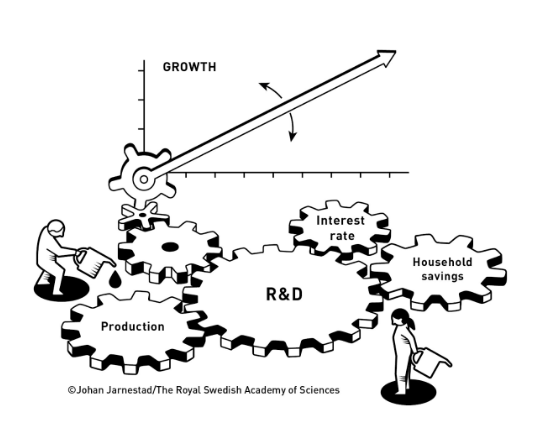

- When a company invests in R&D and creates a superior product, it gains temporary monopoly profits. These profits attract competitors to innovate further. New products soon replace the old ones. Together with this continuous cycle of innovation drives growth from within the economy—capturing the essence of endogenous growth theory.

- In general, the Aghion–Howitt model highlights that temporary monopoly power is crucial for economic growth. Firms invest in R&D primarily because they anticipate short-term market dominance. However, it allows them to recover their costs. To emphasize, without this incentive, innovation would be stifled. However, the monopoly must remain temporary. If established firms prevent new entrants, the cycle of innovation is disrupted, and growth slows.

- However, their mathematical model analyzed how individual decisions and conflicting interests at the level of firms lead to steady economic growth at the national level.

- For example, in the US, over ten per cent of all companies go out of business every year, and just as many are started. Consequently, among the remaining businesses, a large number of jobs are created or disappear every year. While these numbers may vary, the pattern of economic growth is the same in other economies as well.

Aghion & Howitt’s Concept of Creative Destruction:

The shared focus, however, was on understanding why humanity achieved sustained economic growth in the past two centuries after remaining largely stagnant for most of history.

Significance of Their Contributions:

Their contributions have immense significances especially for Policy implications

- Firstly, they highlight whether governments should provide subsidies for R&D in companies.

- In addition, they help to analyse how these steps will help the society or the company.

- In addition, they also help to analyse whether governments should subsidise social welfare and create a social safety net to ensure the society does not lose its openness to change.

- The Nobel laureates’ work highlights that sustained and inclusive growth requires both incentives for innovation and robust social safety nets. Both of them complement each other.

Contemporary Relevance:

- The 2025 Laureates’ framework provides insights into contemporary economic challenges for India and the world.

- Further, Aghion has cautioned that artificial intelligence firms could gain disproportionate control. However, it may potentially block opportunities for new innovators.

- Aghion also warned that new tariffs and de-globalization pose risks to global growth. Coupled with this, protectionist measures shield domestic firms from the creative destruction driven by international competitors. Furthermore, it undermines sustained economic progress. This aligns with Mokyr’s historical insight that openness to new ideas and international trade is essential for long-term economic development.

List of Winners of Nobel Prize in Economics Since 1969 To 2025:

| Year | Laureates | Contribution |

| 1969 | Ragnar Frisch, Jan Tinbergen | For developing and applying dynamic models for analysis of economic processes. |

| 1970 | Paul A. Samuelson | For developing static and dynamic economic theory and raising level of analysis. |

| 1971 | Simon Kuznets | For empirical interpretation of economic growth and social structure. |

| 1972 | John R. Hicks, Kenneth J. Arrow. | For contributions to general economic equilibrium and welfare theory. |

| 1973 | Wassily Leontief | For development of input-output method and application to economic problems. |

| 1974 | Gunnar Myrdal, Friedrich von Hayek | For pioneering work in theory of money, economic fluctuations, and interdependence of phenomena. |

| 1975 | Leonid V. Kantorovich, Tjalling C. Koopmans | For contributions to theory of optimum allocation of resources. |

| 1976 | Milton Friedman | For achievements in consumption analysis, monetary theory, and stabilization policy |

| 1977 | Bertil Ohlin, James E. Meade | For contribution to theory of international trade and capital movements. |

| 1978 | Herbert Simon | For research into decision-making within economic organizations. |

| 1979 | Theodore W. Schultz, Sir Arthur Lewis | For pioneering research into economic development of developing countries. |

| 1980 | Lawrence R. Klein | For creating econometric models for economic fluctuations and policies. |

| 1981 | James Tobin | For analysis of financial markets and relation to expenditure, employment, production, prices. |

| 1982 | George J. Stigler | For studies of industrial structures, markets, and effects of public regulation. |

| 1983 | Gerard Debreu | For incorporating new analytical methods and reformulating general equilibrium theory. |

| 1984 | Richard Stone | For contributions to development of national accounts for empirical economic analysis. |

| 1985 | Franco Modigliani | For pioneering analyses of saving and financial markets. |

| 1986 | James M. Buchanan Jr | For contractual and constitutional bases for economic and political decision-making. |

| 1987 | Robert M. Solow | For contributions to theory of economic growth. |

| 1988 | Maurice Allais | For contributions to theory of markets and efficient utilization of resources. |

| 1989 | Trygve Haavelmo | For probability foundations of econometrics and analysis of simultaneous economic structures. |

| 1990 | Harry M. Markowitz, Merton H. Miller, William F. Sharpe | For pioneering work in theory of financial economics. |

| 1991 | Ronald H. Coase | For clarifying significance of transaction costs and property rights. |

| 1992 | Gary Becker | For extending microeconomic analysis to human behaviour including nonmarket behaviour. |

| 1993 | Robert W. Fogel, Douglass C. North | For renewing economic history research with theory and quantitative methods. |

| 1994 | John C. Harsanyi, John F. Nash Jr., Reinhard Selten | For pioneering analysis of equilibria in non-cooperative games. |

| 1995 | Robert E. Lucas Jr | For developing and applying rational expectations, transforming macroeconomic analysis. |

| 1996 | James A. Mirrlees, William Vickrey | For contributions to economic theory of incentives under asymmetric information. |

| 1997 | Robert C. Merton, Myron Scholes | For a new method to determine the value of derivatives. |

| 1998 | Amartya Sen | For contributions to welfare economics. |

| 1999 | Robert Mundell | For analysis of monetary and fiscal policy and optimum currency areas. |

| 2000 | Daniel L. McFadden | For theory and methods for analyzing discrete choice. |

| 2000 | James J. Heckman | For theory and methods for analyzing selective samples. |

| 2001 | George A. Akerlof, A. Michael Spence, Joseph E. Stiglitz | For analyses of markets with asymmetric information. |

| 2002 | Vernon L. Smith | For establishing lab experiments as a tool in empirical economic analysis. |

| 2002 | Daniel Kahneman | For integrating insights from psychology into economic science. |

| 2003 | Clive W.J. Granger | For analyzing economic time series with common trends (cointegration). |

| 2003 | Robert F. Engle III | For analyzing economic time series with time-varying volatility (ARCH). |

| 2004 | Finn E. Kydland, Edward C. Prescott | For contributions to dynamic macroeconomics and business cycles. |

| 2005 | Robert J. Aumann, Thomas C. Schelling | For understanding conflict and cooperation through game theory. |

| 2006 | Edmund S. Phelps | For analysis of intertemporal tradeoffs in macroeconomic policy. |

| 2007 | Leonid Hurwicz, Eric S. Maskin, Roger B. Myerson | For laying the foundations of mechanism design theory. |

| 2008 | Paul Krugman | For analysis of trade patterns and location of economic activity. |

| 2009 | Oliver E. Williamson | For analysis of economic governance, especially boundaries of the firm. |

| 2009 | Elinor Ostrom | For analysis of economic governance, especially the commons. |

| 2010 | Peter A. Diamond, Dale T. Mortensen, Christopher A. Pissarides. | For analysis of markets with search frictions. |

| 2011 | Thomas J. Sargent, Christopher A. Sims. | For empirical research on cause and effect in the macroeconomy. |

| 2012 | Alvin E. Roth, Lloyd S. Shapley | For theory of stable allocations and market design. |

| 2013 | Eugene F. Fama, Lars Peter Hansen, Robert J. Shiller | For empirical analysis of asset prices. |

| 2014 | Jean Tirole | For analysis of market power and regulation. |

| 2015 | Angus Deaton | For analysis of consumption, poverty, and welfare. |

| 2016 | Oliver Hart, Bengt Holmström | For contributions to contract theory. |

| 2017 | Richard H. Thaler | For contributions to behavioural economics. |

| 2018 | Paul M. Romer | For integrating technological innovations into long-run macroeconomic analysis. |

| 2018 | William D. Nordhaus | For integrating climate change into long-run macroeconomic analysis. |

| 2019 | Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Michael Kremer | For experimental approach to alleviating global poverty. |

| 2020 | Paul R. Milgrom, Robert B. Wilson | For improvements to auction theory and inventions of new auction formats. |

| 2021 | Joshua D. Angrist, Guido W. Imbens | For methodological contributions to analysis of causal relationships. |

| 2021 | David Card | For his empirical contributions to labour economics. |

| 2022 | Ben Bernanke, Douglas Diamond, Philip Dybvig | For research on banks and financial crises. |

| 2023 | Claudia Goldin | For advancing understanding of women’s labour market outcomes. |

| 2024 | Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, James A. Robinson | For studies of how institutions are formed and affect prosperity. |

| 2025 | Joel Mokyr; Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt | “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth” One half to Joel Mokyr “for having identified the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress” Other half jointly to Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt “for the theory of sustained growth through creative destruction.” |

Indian Origin Winners of Nobel Prize in Economics:

- 1998 – Amartya Sen (US citizen, was born in Santiniketan, West Bengal, India) – For contribution to welfare economics.

- 2019 – Abhijit Banerjee (US, born in Krishnanagar, West Bengal) – For his experimental approach to alleviating global poverty.

Conclusion:

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics does not only highlight how humanity overcame centuries of economic stagnation. It also identifies the forces that could threaten continued growth. Specifically, Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt show that modern economic growth is a dynamic cycle of creation and destruction due to cultural foundations and proactive governance.

Sources:

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2025/press-release/

- https://indianexpress.com/article/upsc-current-affairs/upsc-essentials/upsc-issue-at-a-glance-nobel-prize-2025-overview-upsc-exam-10320611/

- https://www.livemint.com/opinion/online-views/nobel-prize-economics-2025-joel-mokyr-philippe-aghion-peter-howitt-innovation-driven-growth-creative-destruction-india-11760711233010.html

Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt jointly received the prize for explaining innovation-driven economic growth.

It is an award established in 1968 by Sveriges Riksbank to honor outstanding contributions to economic science and understanding of societal welfare.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences selects the laureates based on their contributions to economic research.

The prize includes a medal, a diploma, and prize money (11 million Swedish kronor in 2025).

Amartya Sen (1998) and Abhijit Banerjee (2019) are notable Indian-origin winners.